Paquibato District, Davao City–As the first column of Red fighters came to view in the open field, marching to the rythmn of drum beats and their commander’s voice prompts, shouts of “Long Live the Communist Party of the Philippines!” and “Long Live the New People’s Army!” broke out from the crowd. Except for the residents of Paquibato District, a known stronghold of the revolutionary movement, many have travelled far to witness this moment: people from different regions in Mindanao, visitors who flew in from Luzon and Visayas, journalists, and even some officials of the Government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP).

It was announced as one of the biggest anniversary celebrations by the CPP, which on December 26 marked its 48th year of waging revolutionary armed struggle. Although similar celebrations were being held in other parts of the country, the highlight here was the battalion formation of the people’s army, which the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) has been calling a “spent force” for years.

But the almost 200 Red fighters who marched out looked anything but spent or close to capitulation or defeat. All eyes were steady and bright in rows upon rows of faces streaked with black paint, their bright red bandannas bearing the golden logo of the NPA in sharp contrast with black camiso de chinos and pants that served as uniforms.

Around the people’s army, people carried flags of revolutionary mass organizations of peasants, women, youth, Moro, OFWs, professionals, and other sectors that make up the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP). In a short while, the flag of the communist party—a symbol of the indomitable worker-peasant alliance—was hoisted up a bamboo pole and flown above all other flags, as everyone sung the Internationale. NDFP consultant Porfeiro Tuna, among those freed at the start of the ongoing peace negotiations with the GRP, congratulated the troops and the people gathered under the mid-morning sun. “Without the people’s army, the people have nothing,” he said, quoting Mao Tse-Tung.

Battalion formation of the New People’s Army. Photo by King Catoy/Altermidya

The Red fighters belonged to the famed Pulang Bagani Command, made up of several company formations operating in the mountain ranges that surround the city center of Davao, Pres. Rodrigo Duterte’s hometown. Brandishing an array of high-powered firearms—M16, AK47, R1, R4 assault rifles and grenade launchers—and ammunition pouches marked with “AFP” and “US”—a reminder that their arsenal comes from hard-fought tactical offensives—they underwent a tactical inspection that included not just a check of their weapons, but of their knowledge of the kind of war they were waging.

“What is the first point of attention in the Three Main Rules of Discipline and Eight Points of Attention?” Tuna asked in Bisaya.

“Speak politely,” the Red fighter answered.

“What is the perspective of the national democratic revolution?” he asked another.

“Socialism,” was the prompt reply.

***

After the field ceremony, the Red fighters visibly relaxed and mingled with the crowd, greeting people and chatting up friends and family. More guests were arriving in droves, aboard trucks, buses and jeepneys, and converging around a stage set in Brgy. Lumiad’s gymnasium.

An estimated 15,000 people attended the National Assembly for Just and Lasting Peace in Brgy. Lumiad, Paquibato District. Photo by King Catoy/ Altermidya

The stage’s centerpiece was a styrofoam cutout of a hammer and sickle, golden with glitter and tastefully adorned with coconut leaves. The backdrop was a colorful mural depicting the people’s unity in the trademark intricate style of revolutionary painter Parts Bagani. The stage set-up included a live video feed and an LED screen for the benefit of the people who have spilled over the back of the gym. Moving graphics of the anniversary celebration’s theme, People’s War is for People’s Peace, flashed repeatedly onscreen.

The program opened with a long chant, a kind of indigenous prayer led by an elderly Lumad, whom I later learned was a datu who had joined the NPA. The event, dubbed by the CPP as the National Assembly for a Just and Lasting Peace, was aimed at explaining and gathering support for the peace talks. And the crowd of around 15,000 seemed to bolster the NDFP’s assertion that the revolutionary movement was negotiating from a position of strength, not of weakness.

The venue itself, a village’s populated center, seems to be a deliberate showcase of this strength. Roughly three hours away from the center of Davao City, one reaches Brgy. Lumiad by traveling through the highway, passing several banana plantations along the way, and turning left where a bamboo pole with a cardboard sign “NPA Checkpoint” bars the way. With a friendly wave from sentinels, the pole is lifted and the bus stops right at the gym. Guests did not have to trek through the mountains at all, for it is a stone’s throw away from the barangay hall, which for the occasion even served as a receiving area for the guests.

The occasion was a time for Red fighters to be with friends and family. Photo by King Catoy/ Altermidya

Paquibato District, where legendary NPA commander Leoncio “Ka Parago” Pitao was based for many years, has an estimated population of 38,000. Most of it is virtually revolutionary territory. Three days before the event, four policemen from the Malabog Police Station came to the village, claiming that they wanted a “drug-free” certification from the village council. The people laughed at their faces, and said that where the NPA is around, there are no drugs. The policemen were allowed entry, but were forced to leave their weapons behind.

For several months now, a unilateral ceasefire has been effect on both sides. But the CPP has reported that counter-insurgency operations, targeting civilians for harassment and intimidation, have continued in the guise of “peace and development” and even “anti-drug” operations within revolutionary territories. The AFP has in turn twitted them, saying that there is no such thing as territories controlled by the communist movement.

In a press conference held at midday, NDFP senior adviser Luis Jalandoni said that the AFP, in violating its own ceasefire, is trying to undermine the strength of the “people’s government” in the countryside, which he claims to be operating in 70 provinces nationwide. Meanwhile, Coni Ledesma, member of the NDFP negotiating panel, said that the Royal Norwegian Government, third-party facilitator for the peace talks, was surprised when the NDFP told them that it is actually the civilian populace who are asking that the CPP’s unilateral ceasefire be lifted, in order to allow the NPA to defend them from military abuses.

It is clear that for the people within the heart of the revolution, peace means more than just the silencing of guns. In fact, the theme of the entire celebration defines peace in the same manner that it defines war: through the epic, unending struggle of the classes. People’s War is for People’s Peace.

***

Ramon, a 66 year-old Manobo, is used to the presence of the NPA. The guerillas have been in his hometown of Arakan Valley, North Cotabato since the 1980s. For him, “Klaro ‘yung NPA ay para sa pobre (It is clear that the NPA is for the poor).”

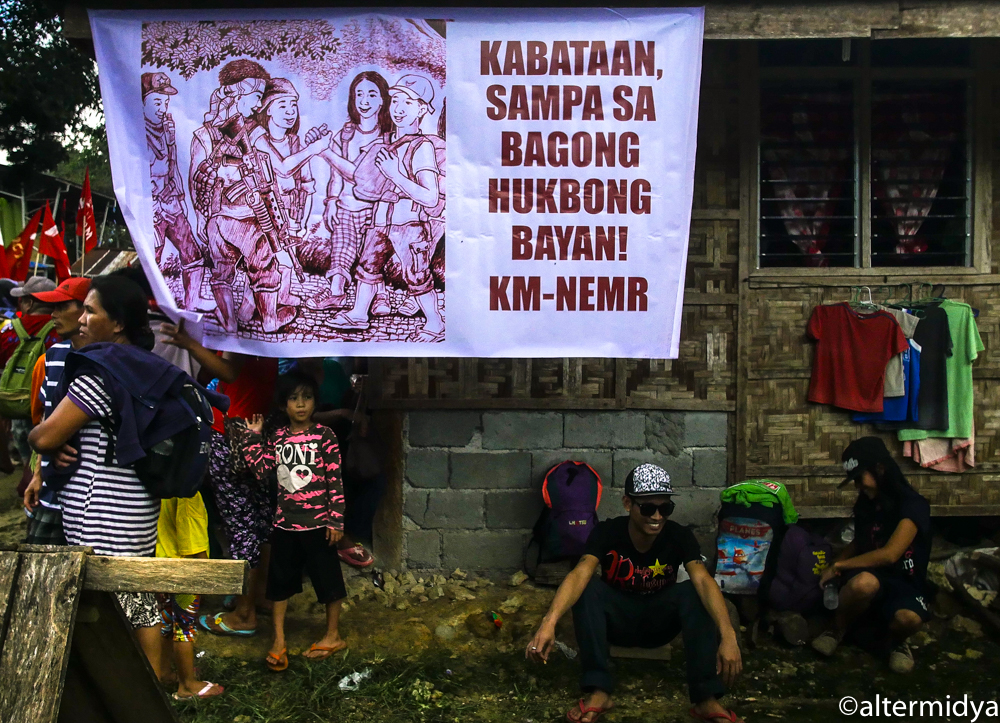

A poster by Kabataang Makabayan encouraging the youth to join the New People’s Army. The minimum age requirement is 18. Photo by King Catoy/ Altermidya

The NPA organizes among the Lumad, and nurture their culture of cooperation and unity, he said. “They help us in food production, solve crimes in our community, and encourage us to build schools for our children.” On the other hand, Ramon said, “The military just harasses us every time we join rallies. They are in favor of big landlords and are used by mining companies and banana plantations.”

Meanwhile, Remedios, a 51 year-old farmer from the neighbouring village is primarily pleased with what she said is the NPA’s positive influence on the youth. “They teach the youth good manners and give them a sense of purpose. So if you ask me, I’m very happy. Of all the people who could help us, they’re the ones who actually do.” She added that the guerillas also help them in the fields and teach them how to lower their costs of production.

For some who attended the celebration, however, it was the first time that they actually laid eyes on Red fighters. Loreta Madrona, a victim of typhoon Yolanda, just recently relocated to Brgy. Paquibato. “In Tacloban City where I used to live, there were no NPA but it was a mess, with drug addicts and thieves everywhere. But here, it’s peaceful. I can even leave my house open and I won’t get robbed,” she said.

Loreta wanted to see for herself the guerillas who they say are responsible for keeping the peace. She often hears about them, but haven’t actually seen them. Now that she has, I ask for her impression. “Okay naman (They’re okay),” she said, smiling shyly. She added that she enjoyed the cultural performances very much.

The performances—a total of seven elaborate dances, several songs by a choir, folk music from a band called People’s Percussionists, and even a rap number with rudimentary break dancing—were indeed, quite impressive. Using bamboo poles and wide swaths of cloth as props, the performers wore jogging pants with brown shirts bearing the logo of Armas, the cultural organization of the NDFP. Their songs and movements mostly depicted rural poverty and exploitation by landlords or mining companies, caricatured U.S. imperialism, and of course, extolled the people’s fighting spirit and revolutionary sacrifice. I was told that most of the performers were Red fighters and their families.

A cultural performance led by the revolutionary group Armas. Photo by King Catoy/ Altermidya

But the production designers, choreographers, and musicians—distinguished by the sequined masks they wore to hide their identity—were mostly students and professionals from the cities. Ka Robert, one of the five choreographers who volunteered for the occasion, is a professional who is sometimes hired by the Department of Tourism to choreograph dances for fiestas. It is clear, however, where his real sympathies lie. “It is satisfying to do this for the masses who really experience what the dances portray. I see the message that I want to convey to them come to life,” he said.

The show, I was told, was the result of two weeks of relentless practice inside the guerilla camp, under sun and rain. For Ka Emma, a 22-year old university student and lead vocalist of People’s Percussionists, being able to perform at her first CPP celebration was a dream come true. She said that what she learned in cultural workshops at school are incomparable to what she learned integrating in rural communities. “Here, poverty and struggle are real. So when the masses and the Red fighters perform, they put their entire heart and soul into it,” she said.

When the Red fighters weren’t performing, guarding their posts, or quietly spending time with their family, they became, like all others, engaged spectators. At one point during the evening, when the marching song Papuri sa Sosyalismo (Ode to Socialism) was performed, red flags waving onstage, some even stood up to band their heads and dance.

Ka Chen, political officer of the 1st Pulang Bagani Company, said that he wished I could have seen the “kitchen,” located in a nearby sitio where 700 cooks have been working tirelessly to feed the thousands of guests. “It’s what the media doesn’t see—it’s not just us. It takes an entire mass movement to hold this kind of event,” he said proudly.

So how much food was needed, I asked? Around 4000 kilos of pork, 2000 kilos of chicken, and 50 sacks of rice for each meal, was the reply. The stocks were mostly donated by allies. Needless to say, nobody went hungry that day.

***

The camp of the Pulang Bagani Battalion lies beside a dirt road a few kilometers away from the gym. Nestled among the mountains, it is a typical guerilla camp dotted with huts made out of black or blue canvas mounted on bamboo poles or tree branches. Littered around these huts were hammocks, boots and backpacks.

Fresh running water was collected in a rectangular basin where everyone bathed, did their laundry, and washed dishes. Down a muddy slope was the makeshift latrine. A visit to the camp a day after the festivities was a sobering reminder of the hardships that accompany waging a revolution. One company, I was told, walked for a month to reach the village.

Camp of the Pulang Bagani Battalion. Photo by Ilang-Ilang Quijano/ Altermidya

Talking to some of the Red fighters, though, one gets the impression that for them, there is nothing difficult that cannot be overcome through praxis. Ka Yuri, 28, is a medic. He describes his job as, “You are always busy. So that when the time for combat comes, everyone is in good shape.” He has already treated two gunshot wounds, but has yet to perform minor surgery, something that he is actually looking forward to. “You just observe at first, and then you practice. It’s not that hard,” he said, shrugging his shoulders.

He joined the people’s army, Ka Yuri said, because of its principles. “Here, we follow certain rules, such as respecting women. And we are respected as well.” In the city, he used to work part-time in construction, called upon by the foreman whenever needed in establishments such as shopping malls. Do you ever think of going back, I asked. He smirked and said, “I’m not interested anymore in that kind of life.”

Ka Bentong, a former student activist, joined the NPA upon finishing high school and reaching 18, the minimum age requirement. He is now 24. Even as he spoke with youthful candor, he already betrays a lot of experience in the armed struggle. “The Lumad are my favorite. They are die-hard supporters of the revolution,” he said matter-of-factly.

He pointed to the nearby mountaintop with a relatively thick forest cover. “In Bukidnon, where I was assigned for two years, there are hardly any forests left. Everything was logged by the company Alson’s. In the 80s, the Manobos there launched a pangayaw or tribal war against the loggers, using only spears, bows and arrows. So when the NPA came, they were very happy. Of course, because they were given guns to defend their lands. What more could they ask for?” he said.

Among those who attended the event are the Lumad. The Lumad are “die-hard supporters of the revolution,” says Ka Bentong. Photo by King Catoy/ Altermidya

Ka Bentong added that imperialism—considered as one of the three basic ills of Philppine society—was very easy to explain to indigenous peoples. “They know imperialism like an old foe. They tell us, ‘they’re the one who stole all our logs,” he said. It is also easy for the Lumad to imagine socialism, he said, as they are already practicing some aspects of it, such as collective farming and decision-making.

Indeed, even without noting the colorful beads that some wore around their arms or necks, it is easy to see that many fighters that make up the Pulang Bagani Battalion were Lumad.

When I asked Ka Betong why he joined the NPA, his answer was very simple: “I want the revolution to win.”

***

Ka Ren, 22, was a laborer for a banana plantation in Davao City. He earned P300 a day, minus wage deductions. “There is no progress for me there,” he said. So he actively searched for comrades. One day, he was finally able to find them, as the ceasefire brought the guerillas closer to the center of villages than usual. Even with guns silent, the NPA continues to attract recruits.

“The masses are often the ones who look for us,” affirmed Ka Chen. An IT graduate and former government employee, he talked about the joys of achieving gains in their land reform program. An example, he said, is how mill owners were forced to lower their milling rates for corn from P2.75 to P2 per kilo, and P6 to P2.50 per kilo for coffee and rice. He cited another example wherein farmer tenants were able to retain two hectares of land and receive monetary compensation for their crops when a landlord was reclaiming their land.

A Red fighter. Phot by King Catoy/ Altermidya

The NPA is often portrayed by the military as ‘extortionists’ who allegedly demand ‘revolutionary tax’ from businesses. But according to Ka Chen, Red fighters do not directly confront landlords or mill owners in pushing for the farmers’ demands. Rather, it is the farmers they organize who do it themselves, becoming empowered with the force of the people’s army behind them.

Most people in revolutionary territories join mass organizations under the NDFP, such as the PKM for farmers, Makibaka for women, and Kabataang Makabayan for the youth, I was told. The organized masses then form part of the leadership of the barrio revolutionary committee—the most basic of the so-called “organs of political power” claimed by the NDFP nationwide, roughly equivalent to a village (barangay) council.

Ka Chen explains that the barrio revolutionary committee is made up of 21 members. One-third are from the basic masses, mostly peasants; one-third from so-called ‘middle forces’ such as professionals and businessmen; and the remaining third are from the Party—representing the ‘proletariat,’ or the international working class.

Officials who each represent the various classes are then elected from the committee. But unlike traditional elections, there is no need for patronage politics or costly campaigns. “People simply vote who they recognize in their community as leaders. They also know that Party members can be criticized if they do something wrong,” Ka Chen said.

These revolutionary committees often function parallel to existing government structures, and has often been referred to as the NDFP’s ‘shadow government.’ “We run programs on education, health, defense, and the economy. Most of the time, people go to us rather than to the reactionary government, so the village council gets the report that it passes on to the DILG (Department of Interior and Local Government) from the revolutionary committee itself,” Ka Chen said with a chuckle.

I’ve heard it said before that when he was still alive, Ka Parago served as the “real” mayor of Paquibato District. There might be some truth to this piece of legend, after all.

***

Building a revolutionary government in the countryside is, however, painstaking work wrought with great, often untold sacrifices. NDFP leaders who are currently engaged in formal peace talks with the GPH under the Duterte administration are well aware of this.

Addressing the people’s army inside their camp on the morning of December 27, Luis Jalandoni cannot seem to contain his joy. Raising his fist, he said, “Revolutionary salute! Your victories, sacrifices, and martyrdom serve as an inspiration to our work. You should know that the people’s war here in the Philippines is one of the strongest in the world. Your struggle is important to liberation movements everywhere.”

Coni Ledesma, meanwhile, congratulated the battalion’s two women commanders, and expressed hope that there will be more women like them. “Because of you, we are slowly building the kind of society we want. A society without exploitation, a society towards socialism,” she told the Red fighters, some of whom allowed themselves to smile even as they were in military formation.

NDFP senior adviser Luis Jalandoni greeting Red fighters. Photo by Ilang-Ilang Quijano/ Altermidya

In the previous day’s press conference, the NDFP leaders bared the increasingly difficult challenges facing the peace talks. Still, they remained optimistic. “Even if we are just able to hammer out an agreement on socio-economic reforms, that would be a big achievement already. Even if it is not implemented, like how the CARHRIHL is not implemented (by the GPH), still we would have a basis to tell them, ‘This is what we agreed upon. This is what should happen,’” Ledesma told the media.

As the sun set and the sky turned dark blue on the day that marked the 48th year of one of the most enduring revolutionary movements in the world, little sky lanterns were brought out. The people shrieked with the delight and novelty of lighting them up. Not all lanterns were correctly filling up with hot air and floating upwards—many wobbled sideways and almost fell. Still, one pair of hands or another would rescue a lantern from crashing and starting a fire. Patiently, someone would wait for it to grow steady until it floats gently into the sky. And although not all lanterns did, most, indeed, lit up beautifully and ascended, countless light-bearers that are always a joyful sight to behold in the gathering darkness of night.

![Paquibato District, Davao City–As the first column of Red fighters came to view in the open field, marching to the rythmn of drum beats and their commander’s voice prompts, shouts of “Long Live the Communist Party of the Philippines!” and “Long Live the New People’s Army!” broke out from the crowd. Except for the residents […]](https://www.altermidya.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/P1110389-1000x563.jpg)

0 Comments